By Brandon Buck

The agency’s filming of its original docuseries, Branchville, spanned over seven episodes, each from 7-12 minutes, and was culled from over 100 hours of footage shot over seven months. As we explored in a previous article, we used a large number of cameras throughout the project and had a wide array of file formats for the footage. From a technical standpoint, the editing process’ organization was greatly assisted by utilizing proxy files to standardize all footage to a format that the computer could easily work with. However, from a creative standpoint, the daunting challenge was how does one go about taking on the herculean task of condensing hours and hours of footage into a coherent story over seven episodes?

For starters, documentary filmmakers create a general sense of the story they want to tell, where they want it to go, and how they would like the story to end — before they commence filming. This way, the filmmakers can schedule their production around the events they anticipate will be needed to tell their story. Some documentaries have famously changed their narrative when their perceived topic changed throughout the production, but this is the main outline of how to set up a documentary.

For Branchville, we followed this same outline in broad strokes: we knew Kevin Summers (our main character, a business executive who returned to his family’s farm to grow hemp) was preparing his land for planting, would plant tens of thousands of hemp seedlings, nurture and care for their growth, and finally harvest the crop for its CBD oil. We knew when these steps would happen throughout the growing season, and scheduled our Savannah-based video production team, Blue Voyage Productions, accordingly. We knew the organizations that would be involved in the farming process: the seedling supplier, the irrigation manufacturer, as well as South Carolina State University Professor of Biology and Environmental Science Dr. Florence Anoruo, who brought in students to test leaf samples, to name a few. We had an agenda of the people we would want to interview; what questions we would ask; and at what point their involvement in the documentary would make the most sense (like presenting the seedling supplier in the episode when the seedlings get planted).

However, we didn’t want the documentary series to be “talking heads” for 10 minutes at a time – all exposition, with very little visual engagement. And some of the same topics would be spoken about several times throughout the year. The key was how to structure the elements to make sure the viewing audience is engaged, and make sure what is covered doesn’t overly repeat itself.

A comparison can be made to shooting wedding videos. Though every special day is unique for the couple, there are a lot of human behaviors that stand the same. This goes especially for wedding party videos, where guests are asked to “say a few words for the bride and groom.” The advice typically goes like this:

1) Hello, I feel awkward on camera.

2) I’m supposed to say something for the bride and groom.

3) I’ll say something silly or embarrassing.

4) But seriously, I’ll say something sweet.

5) Congratulations.

And for a party video that will only be a few minutes, this is fine, especially if a lot of people need to be included in the final video. So, we treated this formula of individual interviews as part-and-parcel for the entire video storyline: we showed several people introducing themselves in one short sequence, several people saying embarrassing things, several people saying something sweet, and then a very quick sequence of everyone raising a toast. This carries the additional flexibility of showing individual people as many or as few times as needed.

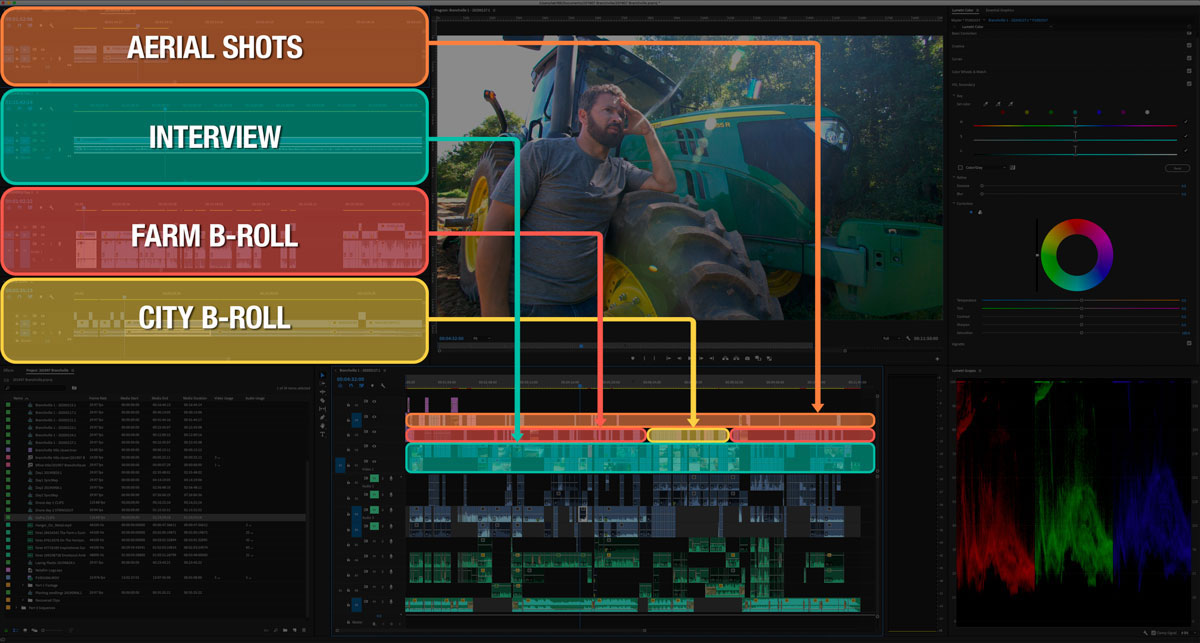

It’s necessary to point out that editing on computers today is a non-linear process. In previous decades, a movie had to exist as a long reel of celluloid film, where the movie physically began at one end of the reel and ends at the other. Editors had to work in a linear fashion: the first scene had to be completed in order to set the stage for the second scene. In contrast, computers only need to know where everything is once the final movie needs to be rendered. As such, editors can build as many sequences, or “timelines,” as they want. Editors can also see all of the timelines simultaneously with a large computer screen. So, in combing through the footage like we would a wedding party, we placed key moments into one of the five different category sequences. Then it was simply bringing all five sequences into one master timeline and editing for taste. This made the job tremendously easier.

Editors working this way have even established a term for it: pancake editing. This is because stacking the long, thin timeline windows vertically can look like a tall stack of pancakes.

In the case of Branchville, the production team filmed the major farming events while including interesting moments filmed throughout the day, such as 20 unique close-ups of hemp plants scattered throughout the 8 hours of footage, having Daron “Farmer D” Joffe describing the certain nutrients for growing hemp in the morning, and having Summers offer his opinion about those same nutrients later in the day. Once we were able to categorize footage broadly into categories like “hemp footage,” “nutrient talk,” “farming challenges talk,” and “prepping equipment footage,” we could compile the outline of a story very clearly. This also meant we were able to compile footage from different shoots into one cohesive topic — for example, the South Carolina Department of Agriculture’s hemp program coordinator visiting the farm after harvesting had begun, even though we wanted the harvesting subject to be the focus of a later episode. Another good analogy is a “salad bar” that allows the customer to assemble their veggies as they walk down the buffet bar.

There are a large number of ways an editor can go about creating their project. Tools are becoming more intuitive and capable than ever before. Still, the best tools are the ones that allow editors to work creatively as they see fit for the project at hand. It is essential to assess tools, not always in the way they were intended to be used, but as to their flexibility required to complete the overall task.